Formatting tricks in MS Word

Posted: October 6, 2013 Filed under: On writing | Tags: agents, formatting, MS Word 2 CommentsI originally posted this over at Aussie Owned and Read in May. I decided my blog needs a few more yawns and a little less excitement (lol), so here it is again for those that missed it.

I can’t decide if this is going to be the most boring blog post in the history of the world, or extremely useful. It may actually be both—I shouldn’t limit myself to a single option, I suppose!

I’m here to talk to you about Microsoft Word formatting tricks to save time when you’re reformatting your manuscripts to meet different agents’ or publishers’ requirements (or so they look correct in blogs; I just had to fix this one using one of these tricks). These tips have all been written for Microsoft 2010, but they work in 1997–2003 as well; they just won’t appear quite the same way on the screen.

Anyway, say you’ve got your beautiful manuscript, and you’ve written it in a standard paragraph format, with an indent at the front of each paragraph. An agent asks you to submit it with no indent and an extra carriage return between paragraphs, like this post. You don’t have to do it all by hand: there are a couple of quick tricks you can use to reformat the entire document in seconds.

The first step is to get rid of the indents at the front of the paragraphs.

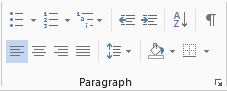

How to access the paragraph formatting box: click the little arrow in the bottom right corner

If you’ve used the hanging indent option it’s easy enough: just select all your text, go into the Paragraph box, and set the indentations to 0pt and none. (If you don’t know, the paragraph box is on the Home ribbon; you access it by pressing the little arrow in the bottom right corner of the box.)

But if you’ve used the spacebar to indent, you need to use the Find and Replace tool. (Press CTRL+F and then click on the down arrow at the far right of the search box and choose Replace.) In the find cell, put the number of spaces you used (say three). Leave the replace cell empty and hit Replace All. That should remove all your indents—although you’ll want to run your eye over it to make sure you haven’t used a different number of spaces anywhere. (This is also the way I reduce two spaces after a sentence down to one.)

Then you need to add that extra carriage return.

This is the sneaky bit. Go back into Find and Replace. In the find cell, write ^p. In the replace cell, write ^p^p. The caret (that’s what the little upside-down v is called) tells Word to look for the paragraph character. Then hit Replace All again.

Ta da! (Okay, I know I’m the only one excited about this, but can you at least pretend to be excited?)

Obviously you can also use this tip to go the other way as well, reducing two carriage returns to one and then adding indents.

Other Find and Replace functions

Other awesome functions of the Find and Replace tool include finding other special characters, and finding specific (or all) text in a certain format. All of these options are accessible from the Find and Replace tool if you click on the button that says More>>. The extra pane that opens up has two more buttons (Format and Special, funnily enough), which open up a world of new options.

-

Searching for an italicised word and replacing it with an unformatted version

For example, in my first manuscript I’d used a few foreign words (okay, words I made up) and italicised them throughout the entire document. But because they were used quite often, I later decided the italics were annoying. I didn’t want to search for every occurrence of the word and fix it by hand. And I also didn’t want to unitalicise the entire document—because I’d used italics for other things, like thoughts.

So I did a find and replace for each of the words formatted with italics, and replaced them with the same word with the font set to “Regular”. What could have been an hour’s work was done in minutes. (You can also search for all examples of italicised/underlined/whatevered text by leaving the find box empty but specifying the format.)

Another example would be if you’ve used tabs to indent your paragraphs rather than spaces or indents, and you want to change it to (say) spaces. If you look in the Special dropdown list, you can see that the tab character is ^t. So if you find ^t and replace with three spaces, Word will take care of it for you.

Format Painter

-

Format Painter: my favourite and my best

The last tool I want to mention is a little gem called Format Painter. You may not use it much in drafting a novel, but it is pure gold for a document with different styles, such as a non-fiction manuscript, essay or newsletter. Format Painter lives on the Home ribbon.

Put your cursor in a block of text with the correct formatting, and then click that button. Then click on the paragraph you want to apply the correct formatting to. Voila! All of the formatting should be applied to the new paragraph. (I say “should” because sometimes it’s a little flaky. But it usually works a treat!)

So, those are my favourite Microsoft Word formatting tips. I hope they help you as much as they help me. Do you have a favourite formatting trick? I’d love to hear about it.

Hey! Are you still awake? *pokes*

He said, she said: dialogue tags

Posted: September 26, 2013 Filed under: On the Isla's Inheritance trilogy, On writing | Tags: editing, Isla's Inheritance, words to be wary of, writing 4 Comments

Source: wiki commons

I mentioned dialogue tags briefly a while ago in a post about “crimes” I commit when drafting—I tend to leave out the name of the other actor in a conversation between them and my first-person main character. It’s one of the things I edit in later.

Here’s a more comprehensive set of thoughts on dialogue tags. Anyone who’s read On Writing by Stephen King will know his advice, but here’s a summary:

- Don’t underestimate the power of “said”. Readers usually don’t notice it, and it lets you anchor the identity of the speaker in the reader’s mind with a minimum of fuss.

- You don’t have to attribute every single line of dialogue. In a back-and-forth conversation between two characters, it’s usually pretty obvious who is speaking for several lines after you include a dialogue tag. And if you have “X said” at the end of every quote, your reader will get annoyed.

- Dialogue tags other than “said” should be used sparingly (see example one, below).

- Consider using character action as part of the same paragraph that contains the dialogue. The action then identifies the speaker.

Example one: too many dialogue tags

This excerpt is taken from Isla’s Inheritance, although I’ve edited it to demonstrate how jarring excessive dialogue tags can be.

“It’s me. Dominic,” he said.

“Dommie?!” I squealed.

“If you must,” he replied dryly.

“I didn’t know you were back!” I exclaimed.

“Got back a few days ago; been catching up with the folks. Hence the lack of effort,” he laughed, indicating his Halloween costume with a wave of his sheet.

“It could have been embarrassing—I almost wore the same thing,” I admitted.

I’ve actually seen poorly edited books that read like this. I sit there wondering whether the author used a thesaurus to avoid repeating the same descriptive word—which means I’ve stopped paying attention to the story and am paying attention to the poor craftsmanship instead.

To make it clear: I’m not saying to never use these words. But I avoid any dialogue tag that doesn’t describe something the reader wouldn’t have gotten from the dialogue itself. For example, “shouted” and “whispered” are okay in moderation, as are “murmured” and “muttered”. But there’s never a reason to use “exclaimed” (because the punctuation mark already indicates that the dialogue is an exclamation), and if you’re using words like “flirted”, consider instead describing the flirtation. (“Hi there,” I flirted doesn’t tell us much; “Hi there,” I said with a wink is much more descriptive.)

Example two: a mix of tags and action

Here is the same sample text as in example one, with minimal dialogue tags, and action used to anchor the reader in the scene. (I also used fewer adverbs.)

“It’s me. Dominic.”

“Dommie?!” I sat up straight.

“If you must,” he said, voice dry.

“I didn’t know you were back!”

“Got back a few days ago; been catching up with the folks. Hence the lack of effort.” He indicated his Halloween costume with a wave of his sheet.

“It could have been embarrassing—I almost wore the same thing.”

Because there are only two characters, I don’t need to attribute every line. It gets more complicated when you’re dealing with multiple characters, but that’s where use of action really comes into its own.

Know the rules before you break them

One technique I noticed Aussie bestseller John Marsden use is not bothering even trying to attribute the dialogue. He used this particular technique when he had a bunch of teenage characters chatting excitedly and it didn’t really matter who was saying what. Stripping all the dialogue tags and action out sped the dialogue up to a sprint, which conveyed the conversation’s sheer chaos.

This is definitely a case where you need to understand the rules before you disregard them, though—the same technique wouldn’t have worked in any of the other dialogue scenes in his book, so he didn’t use it there.

Variety is key

As with most things in life, the best guide for dialogue tags is “everything in moderation”. If you mix up “said” with other dialogue tags, no dialogue tags and action, you’ll have a pretty solid foundation for conveying your dialogue and furthering your story.

Naming your book – and naming my book!

Posted: September 18, 2013 Filed under: On the Lucid Dreaming duology, On writing | Tags: editing, Lucid Dreaming, writing 5 CommentsLet me start out by saying that I suck at naming my books. Seriously. I come up with working titles during the drafting stage that don’t work for one reason or another, and then I get to the end of the process and can’t think of anything else.

For example, Isla’s Inheritance originally had a title that actually contained a (minor) spoiler. I know, right? I’m an idiot. The working title was a great title—just not for that book. (I may use it for the third book in the trilogy; that remains to be seen.) The second book in the series was “Book Two” for ages, till it eventually became Isla’s Oath after Sharon suggested it.

For example, Isla’s Inheritance originally had a title that actually contained a (minor) spoiler. I know, right? I’m an idiot. The working title was a great title—just not for that book. (I may use it for the third book in the trilogy; that remains to be seen.) The second book in the series was “Book Two” for ages, till it eventually became Isla’s Oath after Sharon suggested it.

Likewise, the book I just finished had a working title that might work for the name of a series, but doesn’t really grab me for the first book (in fact, I just googled it and it already is the name of a series … so that’s not going to work either, gorramit!). So I’ve been noodling new ideas for the past few weeks as I’ve been editing, settling on my criteria for a good book name.

These are my thoughts.

1. It shouldn’t have the name of a well-known book.

This point is pretty obvious. Bestsellers receive more promotion—anyone who walks into a store looking for your book may come out with the bestseller the bookseller has heard more about. (We’re not talking about your hardcore fans here, because they’ll know the author—but it’s amazing the number of people who buy gifts or hunt for books based on a fragment of information!)

For example, I thought about calling Isla’s Inheritance simply “Inheritance”, but Christopher Paolini already did that for his last Eragon book. Rats. If you’re not sure who else has used your potential title, Goodreads and Amazon searches are your friends.

I’ve been agonising about whether it’s okay for my book to share a title with any other work of fiction. If there’s an obscure self-published novel with only one or two ratings that has the same title, is that okay? I’m thinking probably. I have more than two relatives I can persuade to rate my book, so I should at least be the more popular one. 😉

One thing you can do, especially on sites like Goodreads, is give your book a subtitle: often the name of the series. Or, for some genres, titles that incorporate a unique, unifying element can work. Harry Potter is taken, though.

2. If it’s part of a series the titles should be thematically related … but also easy to remember.

As much as I’m not a huge fan of the Twilight series, Stephanie Meyer—or her editor—deserves huge amounts of respect for coming up with an awesome series of book titles. They are connected but not samey. You know which book is which. And they are short, which makes them easy to remember.

Maybe it’s just me, but I find a long series where the titles are all too close to one another very confusing. Charlaine Harris’s Sookie Stackhouse series of thirteen books is a good example. All of the books have the word “Dead” in the title. I just couldn’t tell the titles apart after a while—which made buying the next one trickier than it had to be! The titles were clever, but distinct? Easy to remember? Not for me, at least.

I haven’t plotted the sequel to my latest book yet—I need to write the third in Isla’s trilogy first—but there will be one. So I want a title that lends itself to that as well.

3. I like titles to be clever and beautiful.

My absolute favourite book titles are the ones that not only sound beautiful but have a double meaning—something where the readers go “oooooooooh!” at some point during the story. Those are hard to come by. Two examples off the top of my head are Bound by J. Elizabeth Hill and Forget Me Not by Stacey Nash (I’ve only seen a draft first chapter of the latter and I already know how perfect that title is for that book).

I love the poetry of Isla’s Inheritance and Isla’s Oath. They both roll off the tongue. But if my editor came up with something that did that and also had a double meaning, I’d give her a big wet kiss and change both titles in a heartbeat. (And of course, unless you’re self-publishing, there’s a good chance the title you’ve agonised over will get changed anyway. I gather this is especially true at the big end of town. But it pays to show you’ve put some thought into it; submitting a manuscript called “Insert Clever Title Here” doesn’t really show you at your professional best.)

So, after all of this consideration, what is the (tentative) title of my latest novel?

(I really wanted a gif with exploding fireworks but I couldn’t find one in the two minutes I spent googling!)

‘Where do you get your ideas?’

Posted: September 15, 2013 Filed under: On the Isla's Inheritance trilogy, On writing | Tags: fanfic, inspiration, Isla's Inheritance, muses, writing 6 CommentsI think the single most common question authors—especially very successful authors—get asked is about their sources of inspiration. The question is almost a stereotype now. And a lot of them reply along the line of, “The real trick is making them stop!”

I used to not understand this answer. I spent a lot of time toying with ideas, usually for high fantasy novels, but never getting far because the well would run dry: the ideas I had felt derivative, or paper thin.

It wasn’t till I said “hell with it” and started writing anyway that I discovered the truth. Like writing skill, the ability to come up with story ideas—for me at least—is like a muscle. The more I write, the more I come up with ideas, the easier it is. I suspect a lot of other writers are the same.

Getting to the point where I had an idea with enough weight for an entire novel was a long process, though. I started out, like a lot of people, writing fanfiction. I wrote some short stories in another writer’s fantasy world; it felt easy to me, because the worldbuilding had been done. This was in the days before the internet was huge (don’t laugh!) so the stories were published in the author’s “official” fanzine and distributed via the post. Old school, yo. *poses*

Then I wrote two or three novella-length stories that were another type of fanfiction: the type with famous people as characters (no, I won’t say who). But the stories were my own. These novellas were about 25k words each; when a friend pointed out to me that if I’d put that amount of effort into real fiction I’d have a novel, it was a sobering realisation. And a motivating one, too. It showed me I could do it, whereas before I’d thought I couldn’t.

So I revisited one of the novellas, and took an extra element of an old (non-fanfic) short story, threw them in a pot, and stirred. Then I started from scratch with the ideas born from this mix. The result was Isla’s Inheritance. The only element from the original novella fanfic that has carried across is one of my original (non-famous) characters: Isla’s cousin Sarah.

And once I finished Isla’s Inheritance, that seemed to open the floodgates on my subconscious. Ideas for a sequel, and another beyond that. Another urban fantasy idea (now finished). A solid fantasy/Steampunk concept (outlined). And other, half-formed ideas.

The muses from Hercules (copyright Disney; source).

These days it seems like whenever I hear a story on the news, or am talking to a friend, part of my brain is turning what I’m hearing over and looking at it from all sides to see whether there’s a kernel of a story idea there. I can see why writers call that their muse. I think of it more as part of myself—but a part I have very little control over. As my friend Stacey Nash describes in her latest blog post, it seems to have a mind of its own.

I’m curious though—do you find it easy to come up with story ideas? Has that always been the case, or have you had to train yourself/awaken the muse, like I have?

Four ways to see your writing anew

Posted: September 12, 2013 Filed under: On writing, Uncategorized | Tags: editing, words to be wary of Leave a comment

A plotters journey: an artist’s impression (image: Wiki Commons)

Drafting a novel is like hiking through a huge forest. Your approach to the impending journey may vary: some of us come up with a detailed map, set their feet on the a path and power on through, while others see the edge of the trees, think “let’s see what’s in there”, and wander in. Most of us have approaches somewhere in the middle: we might know where we want to end up, but not have a specific path in mind. Almost all of us get distracted by things along the way; sometimes the distractions turn out to be just that, while other times they are a valuable addition to your journey.

But there’s an idiom that also applies to a writer who is in the middle of or has just finished drafting a novel.

I can’t see the forest for the trees.

Whether you love your work or hate it, when you type THE END, you are not seeing it clearly. Everything from being able to discern the dead wood, those scenes, characters or chapters that don’t move the story forward, to spotting typos is harder. You don’t have the altitude. You’re still in the trees.

So here are four ways to see your work differently: to get a Google maps perspective on your forest.

1. DO SOMETHING ELSE!

This is the first and most important, which is why I gave it shouty caps. If you can possibly avoid it, don’t jump straight back into editing. Give the manuscript a few weeks to stew. Read a book (or five). Write something else. Go on holiday. Spend some time with the loved ones you’ve been neglecting. You’ve written a novel, which is a thing to be proud of. Celebrate, but not by re-reading it.

This point should be applied in conjunction with one or more of the other suggestions, below. The only exception is if you’re up against a hard deadline that doesn’t give you the luxury of time. I’m not talking about a pitching contest you want to enter—there will always be more pitching contests—but something with legal ramifications, like a contractual requirement.

2. Read it in hard copy.

Speaking of trees (sorry about that, forests of the world)… This is my favoured approach. I wish I could get the necessary distance while still reading my words on a screen, but that’s the place where I drafted it, and I just can’t. On paper I can see misspelled or misused words, tracts of exposition—they all leap out at me. Usually I do a dirty word search before I hit print and make those amendments to the soft copy (looking for the crimes against English that I know I commit when drafting). Then I sit down with a pen and have at it.

This does have the drawback that I have to enter my edits onto the soft copy afterwards. It’s tedious but, for me, worth it.

3. Change the appearance of the words.

If you draft in Arial, try looking at your manuscript in Times New Roman. Or Comic Sans MS, if that’s what floats your boat—just remember to change it back before you submit it to any agents or publishing houses. I know some people who actually format their book and read it on their Kindle, to try and put themselves into the role of a reader rather than the author.

As an aside, I do this with all my blog posts. I write them in Word, do one proofread in the WordPress data entry screen, and then do a final check in the blog preview screen.

4. Read it aloud.

Obviously this is better for picking up line edit problems—passive sentences, overused words, that sort of thing—rather than structural problems. Although if you get bored reading a scene maybe that’s a sign the scene could go. There are also text-to-speech programs that you could use if you don’t want to read your 150,000-word opus aloud for fear of never being able to speak again. (And, um, if that’s your first novel I also recommend reconsidering the length.)

I’m tempted to add a fifth point here that says “see point one”, but I won’t. You get the idea.

Do you have other tricks that you use to let you see your words afresh?

Editing: my four (well, five) writing weaknesses

Posted: September 6, 2013 Filed under: On writing | Tags: aussie-owned, editing, writing 11 CommentsBefore we start, have you guys read my interview with the awesome Steampunk writer Jay Kristoff over at Aussie Owned and Read? If not, it’s here. Go on, I can wait.

An overworked train metaphor, chugging away… (Image via Wiki Commons)

Since I finished my most recent work-in-progress, I’m back on the editing train, steaming my way from the tiny villiage Stream of Consciousness to the (hopefully) shiny metropolis Compelling Prose.

(Fact: sometimes “steaming” can also be applied as an adjective to my first drafts!)

One of the things that makes you a better editor of your work is to know your writing weaknesses—the crimes you commit against the English language when you’re caught up in the initial drafting rush—so you can spot and fix them. Here are a few of mine, to give you an idea of what I’m taking about.

I LOVE the word “that”. Love it. In my first book, there were hundreds of unnecessary uses. I’m getting better but it’s still a problem. I use it when it’s necessary, when it’s unnecessary, and when it’s just plain wrong—for example, when I should instead say “who”, I say “that”. Every time. When I finished my manuscript a fortnight ago, I did a search for the word “that” and checked each usage.

It took hours.

I describe impossible bodily actions. My characters’ eyes do all sorts of things they shouldn’t. They roam the room instead of staying in their sockets where they are meant to be, the cheeky little sods. So I search for “eyes” and make sure to change it to “gaze” (or similar) when I’ve used it in that context.

As an aside, I’ve seen a senior editor suggest the word “blush” causes a similar problem in first-person books. Blushing is actually a reddening of the cheeks, and the first person character can’t see her own cheeks to know they reddened; she feels her cheeks burn, but can’t see it. This editor consequently said not to say “I blushed”. One to watch out for.

I describe redundant body parts. “He shrugged his shoulders”; “she nodded her head”. Given these are the traditional body parts to use, mentioning them is redundant. The only time you should mention the body part in these cases is when the character is using an atypical part—for example, nodding a hand during a puppet show.

Likewise, saying a first-person (or close-perspective third-person) character “saw” or “heard” something is almost always unnecessary. Given they are telling the story, if you describe something to the reader it’s implicit that the character noticed it.

He said, she said. When I’m describing dialogue between two characters in the first person, I can go for ages without mentioning the name of the second character. It’s all “I said, he said”. My solution to this is, again, to search for the character name and scan through the section of dialogue. Word 2010 highlights any found words in yellow, so if I see a whole page with no yellow, that’s a sign it needs review.

Complex sentences. I love these too. I go nuts with the ands, commas, dashes and semicolons to link ideas together. Sometimes it’s not a problem, but other times—such as during fight scenes or other adrenalin moments—a long sentence slows the action down. When I edit, I find these scenes and chop the sentences up, sometimes even into fragments.

So, those are my main writing sins—and yes, you got five instead of four. Counting? Me?

What are your writing weaknesses?

A big moment for me…

Posted: August 21, 2013 Filed under: On me, On writing | Tags: aussie-owned, Interview, university, writing 3 CommentsMany years ago, I did professional writing at university. I landed there because in year twelve I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do with my life, and a very lazy career adviser said, “Well, what classes do you enjoy?” and I said, “Um, English?”

I also enjoyed computing, so if the career adviser had asked a slightly different question or if I’d mentioned the other class first I might be a highly paid IT nerd right now. I’d still be writing, regardless, but maybe not quite as well. (Much love to any IT nerds reading this. My boyfriend is one; I mean no disrespect.)

As it was, I got a degree that was broadly applicable to every job I had — I draft a mean minute — but only became specifically applicable in the last five years when I landed my precious editing job, and started writing again.

The head of the course — let’s call her Janey — was a huge fan of literary, feminist fiction. Genre fiction fans like me didn’t get a lot of credit from her, and the male genre fiction fans in the class got even less. She also believed in what she probably would’ve called tough love, but what I secretly believed was her way of trying to scare us all into not bothering to write so that she had a better shot at getting her own Great Australian Novel published.

I remember one lecture where Janey was talking about the Australian publishing industry. She told us there were maybe half a dozen Australian fiction writers who could make a living off their work, that they all wrote literary or mainstream commercial fiction (ie they were Bryce Courtenay), and that we should all give up any hope of ever being successful enough to pay a mortgage.

Especially us genre fiction writers.

I have no words

(Note: Her advice is both good and very crappy. Kids, don’t give up your day job to write unless you are independently wealthy or you’re already earning enough from your existing royalties to pay the bills and save for your superannuation. But don’t believe it’s not possible to achieve the latter with a lot of hard work and persistence, either.)

Anyway, a few years later I discovered Kate Forsyth.

Kate is a Sydney writer. She writes speculative fiction. She is very good at her job, and she makes a living from it. When I read her high fantasy series The Witches of Eileanan, I loved the story — but who Kate was and what she was doing was, simply put, a revelation.

And yesterday I got to interview her over at Aussie Owned and Read.

Take that, Janey.

Inspired by butterflies (and moths, and deviantART)

Posted: August 15, 2013 Filed under: On writing | Tags: Thursdays Children 9 CommentsI thought about writing a Thursday’s Children post about being inspired by Pinterest, but that’s pretty much a gimme. I did use it as a source of inspiration over the weekend, when I was struggling with visualising something, but there was another source I used even more.

Image from Wiki Commons

Have you ever heard of the website deviantART? It’s a place where artists can post their visual (and sometimes written) art for others to admire and, if they’re so inclined, purchase.

Well, I went to dA, and found some AWESOME art. (I even then pinned it to my board–see how those things come together?)

Without going into too many details, my work in progress has a certain insect-y theme. I’d been using moths till now, but decided to mix it up a little with what I thought was an Australian butterfly: the Monarch (aka Wanderer). It turns out the Monarch is from the US and has just wandered its way over here. Like a flying cane toad.

They’re even poisonous, apparently, because of the plant they prefer to eat, the milkweed. Things I didn’t know.

Anyway, some of the images I found on dA by searching for Monarch Butterflies were breathtaking. I’d love to post them here, but copyright, so instead here are a few links. Click them. CLICK THEM NOW!

Monarch by *RozennIlliano

Monarch by *RozennIlliano

:MonarcH: by *AkiMao

Monarch by ~CloudyNine

Monarch by `Emerald-Depths

Click here to see this week’s other Thursday’s Children blog posts.

On themes and dinosaur bones

Posted: August 6, 2013 Filed under: On the Isla's Inheritance trilogy, On writing | Tags: Chuck Wendig, Isla's Inheritance, theme, urban fantasy, writing 2 CommentsI’ve written almost three novels now, but I’ve never consciously developed a story’s theme as I was writing it. I always felt a little guilty about that, because everyone tells me that theme is one of those things that binds a story together. Like grammar, or pacing, or dialogue tags.

My current work in progress is at 69k words (dude) and I’m at the start of the final confrontation scene. I’m having a moment of what I could call writer’s block, except I don’t feel blocked—I feel more like an archaeologist who’s revealed a small part of the skeleton and is dusting away at it with a little brush to reveal HOLY CRAP IT’S A FREAKING DINOSAUR!

The final scene of my book: an artist’s impression (image from Wiki commons)

The reason I wouldn’t call it writer’s block has a couple of elements:

1. I know which characters are involved in the scene, and what the inter-personal dynamics are.

2. I know who is going to win and what the final outcome will be.

What I don’t have yet is the how. How are they going to win? I’ve been pondering this for a couple of days, and it dawned on me that the other thing I know about the scene is that I want them to win not by dint of awesome superpowers (I write urban fantasy, so there are a few of those kicking around) but by virtue of accessing the part of them that is human.

And then I realised tonight, HOLY CRAPBISCUITS! THAT’S MY BOOK’S THEME!

In fact, it’s been a theme of all three of my books—both of Isla’s stories and this latest one (which is about a different character).

My books are about people struggling with what it is to be human and other, and to become an adult, all at the same time. And that’s kind of cool.

Although maybe not for my characters.

As is often the case, Chuck Wendig says it best. (Check out point three: apparently I don’t have to feel bad about not writing it in consciously after all. Phew!)

Now excuse me—I have to go back to dusting these dinosaur bones.

Coming home

Posted: August 1, 2013 Filed under: On me, On writing | Tags: real-estate, Thursdays Children 7 Comments After a week and a half of packing and more packing, and then moving and more moving, my son and I are out of the place that’s been our home for the last three years. I wish I could say I was emotional about it, but the only emotion I feel is relief.

After a week and a half of packing and more packing, and then moving and more moving, my son and I are out of the place that’s been our home for the last three years. I wish I could say I was emotional about it, but the only emotion I feel is relief.

Maybe that’s a side effect of packing a four-bedroom house on your own. The exhaustion leaves no room for anything else.

We’re temporarily staying at my parents’ place for the next month or so. They are out of the country, so it’s just my boy and I. He’s sleeping in what was my childhood bedroom. I’m in my sister’s old room (the latter was fully furnished, and I figured my son would adapt better if he had his own bedroom furniture).

This is the house I grew up in, in the suburb I grew up in.

We won’t be here for long, but it really felt like coming home.

I don’t think most adults learn their neighbourhoods the way a child does. Kids explore all the back alleys and parks during their romps; they know where the blackberry bushes grow over the fence to be plundered, or where the plum trees are. They know which path to avoid in spring when the magpies are swooping, exactly how the tree trunk at the local park can double as a rocketship, and where to find willow fronds to weave into headbands.

I think I’m going to miss this place when I move, possibly more even than the house I just sold. Don’t get me wrong. I loved that house. It was beautiful and spacious. But it was also the source of a lot of stress–my ex-housemate and I regularly joked that its extension had been built on a hellmouth.

As a result of all the packing and moving, I haven’t written in two weeks. I’m starting to feel extremely twitchy, especially as my WIP is at the point where I’m about to write the final confrontation. I was really looking forward to it, too. Of course, Murphy’s Law being what it is, I got sick halfway through the move, so I’ve had to hold off a few more days–at least until the fever subsided.

But you know what? When I get to write again, that’s going to feel like coming home too.

Click here to see this week’s other Thursday’s Children blog posts.